Avast Business Team 3 Apr 2024

Avast Business Team 3 Apr 2024

Scammers use psychology to create some of the most convincing internet cons – here's how to advise your customers on what to watch out for.

Today’s most common crime is not burglary, car theft or even shoplifting - it’s online fraud. And this includes pitfalls such as emotional scamming. Not to mention, anyone with an internet connection (in other words, all your customers) is a potential victim. So what do you need to know, and how can you advise your customers, to help keep them safe online from this particular kind of scam?

Emotional scamming is a sophisticated kind of online fraud that exploits human psychology to achieve its aims. We all have biases and psychological blind spots that make us susceptible to scammers, which is why even people who consider themselves ‘intelligent’ can still be deceived if they are approached in a way which gets under their radar.

Specifically, the key emotional scams to be aware of are:

Let’s examine each one, along with the steps your customers can take to avoid becoming a scammers’ next victim.

And though Avast researchers have detected a sharp uptick in romance scams, there are steps you can take to avoid becoming a victim.

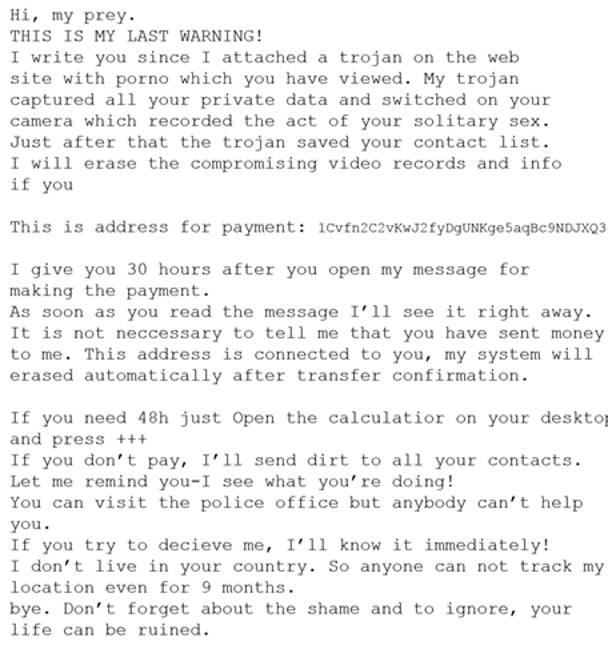

This is old-fashioned blackmail brought up to date and exploiting the same old vulnerabilities: sex and the threat of exposure. It begins with an email such as this one:

Despite the poor English, receiving this kind of email can be frightening. First, it makes specific threats. Second, it uses some fairly believable terminology (‘my trojan captured all your private data and switched on your camera’). And third, it plays on the kind of fears around technology which those without much tech knowledge may wonder about, like whether someone can remotely access and record a webcam.

The most important thing you can tell a customer who has been threatened in this way is to not respond at all. The next is to reassure them that this kind of email is generally not based on truth. In 99% of these cases, there is nothing to expose.

A scammer remotely accessing and recording someone’s webcam is highly unlikely. Remote access without permission is possible, but it would require the presence of downloaded malware that came from a malicious site on the owner’s computer.

Many of these emails augment the fear factor by appearing to come from the victim’s own email address. This makes the approach seem personally targeted rather than random. However, it is relatively simple for a scammer to manipulate the ‘From’ field in an email, and is a well-known trick to make it appear that they have access to the recipient’s computer and data.

Sometimes the email may include one of the recipient’s old passwords. Again, this is simply a method of increasing the apparent authenticity of the scammer’s claim to have access, but in reality, it is meaningless. The password will have been acquired through a data breach rather than directly from the recipient. If it is out of date and hasn’t been used by a hacker, then it is no more of a threat than using the recipient’s email address.

One thing to note is that the email doesn’t use the victim’s name. Regardless of how individually targeted it appears, this is another indication that it is a mass-mailed scam.

Also, the recipient’s phone number being included in the email can be equally frightening. But it is not evidence that the scammer has more useful information about the victim. Phone numbers can be acquired from data breaches just as passwords can – and since phone numbers change less often, it’s more likely they will be current. It’s also unlikely that the scammer would ever escalate to making telephone contact. So recipients can simply ignore, delete, and forget the email, without expecting things to progress any further.

However, this doesn’t mean that the scammer won’t try again. There may be some kind of countdown or time limit included in the email. If the scammer receives no response, they can use this to increase the pressure. Alternatively, they may claim they are offering more time to give the recipient another chance. This could go on for days or even weeks. The best option is to block the emails, delete them as soon as possible, and forget about them.

There is a possibility that a customer receiving one of these emails is actually being personally targeted. They may have previously interacted with the sender in some way. If this is the case, then this is blackmail and the customer should notify the relevant authorities.

Obviously not what it sounds like, but just as unpleasant. The name comes from the way that the victim is ‘fattened-up’ by being fed affection, before being ‘slaughtered’.

This is a long-term scam that often starts with a text, social media message, or introduction through a job board site. The scammer starts slowly, gaining the victim’s trust, and then ultimately leading to an online ‘romance’ which often involves constant email contact. However, this is all a ‘fattening-up’ (or softening-up) for the next stage of the scam, which proposes an investment of some kind – usually in cryptocurrency.

Fake platforms and websites will be used to show the victim’s supposedly successful returns, but in reality, the money ‘invested’ is going straight to the scammer. The victim will be encouraged to invest more and more heavily – and this is where the psychological aspect comes into play. Research shows that people will ignore signs that things are not going in their favor if they have already spent substantial money, time, and effort. To put it another way, people are more likely than not to ‘throw good money after bad’.

However, when the victim runs out of money to ‘invest’, or tries to withdraw some of their ‘profits’, they will be blocked and unable to contact their scammer. The supposed romantic relationship aspect of the scam often leaves victims too embarrassed to admit it to friends and relatives, or to report it to the authorities.

A recent news story about a scam that began via Tinder illustrates “pig butchering.”

The scam began via Tinder, where a professional chef was matched with a woman who introduced him to her ‘uncle’, a supposed professional cryptocurrency trader. Starting with just £850, the chef ultimately ‘invested’ £40,000 which he was inevitably unable to reclaim when both his Tinder date and her uncle disappeared, and blocked his messages.

Another flaw in human psychology is to always trust authority. So, your customer may be inclined to believe an email that’s apparently from a payment app, whether it tells them that they have received a payment or have overpaid, have suspicious activity on their account, need to verify their account, or makes one of several other spurious claims. The aim is to get the potential victim to click on a link, or occasionally to call a number where the scammer will use their apparent legitimacy as an employee of the payment app company to extract valuable customer information for fraudulent purposes.

Alternatively, it there is a link to click on, it will lead to a fake website with a legitimate-looking address and appearance, where the victim will be asked to enter their account information and password. This is all the scammer needs to access and exploit the victim’s account.

Another scam which – whether the scammer is really aware of it or not – uses psychological techniques to lure in the victim. It exploits innate kindness, and the tendency of people to follow and copy the behavior of others.

An initial post poses as a plea to help find a missing person. There is, of course, no one missing. However, people will be inclined to like and share the post, which increases its credibility.

The scammer will then edit the content so that the likes and shares now appear to be lending credibility to an investment scheme. The bait has been set, and the scammer is now ready to attract money from gullible potential investors who are reassured by the seeming endorsements of the edited post, which have actually been ‘stolen’ from the original missing person post.

If the initial missing person story is examined more closely, it can be easy to identify flaws. For example, one such scam reported a missing girl – but depending on the post you saw, reported her as missing in Cambridgeshire or Wales. The post also included a photograph of a girl who had actually previously gone missing, but in Ohio – and she was subsequently found.

A natural trust of authority is the psychological emotional flaw exploited by this scam.

A mobile app posted on the Google Play or Apple app store gains legitimacy simply because it is available from a legitimate site. Even a fake app posted here will often have a genuine function. But this will merely be a shield to hide the fake apps’ main purpose: stealing users’ personal information once downloaded.

An example, recently identified and removed from the Apple App Store, is the ‘LassPass Password Manager’, which relied on the trust invested in the genuine LastPass app.

Emotional scamming exploits deep-seated human traits such as the need for affection or a trust of authority. Scammers also rely on people failing to take the time to read emails carefully, or to spot small differences, flaws, or changes in – for example – website URLs and the websites themselves.

They depend on the embarrassment factor, which makes victims less likely to discuss the potential scam with others until (or even when) it’s too late. This may also prevent victims from reporting the scam to the authorities – which lets the scammers scam another day.

Your advice could make the difference between your customer becoming a victim or the one that got away.

1988 - 2026 Copyright © Avast Software s.r.o. | Sitemap Privacy policy