Avast CTO, Ondrej Vlcek, looks back at the year since WannaCry hit and asks if the tech industry has done enough to prevent another such cybersecurity incident.

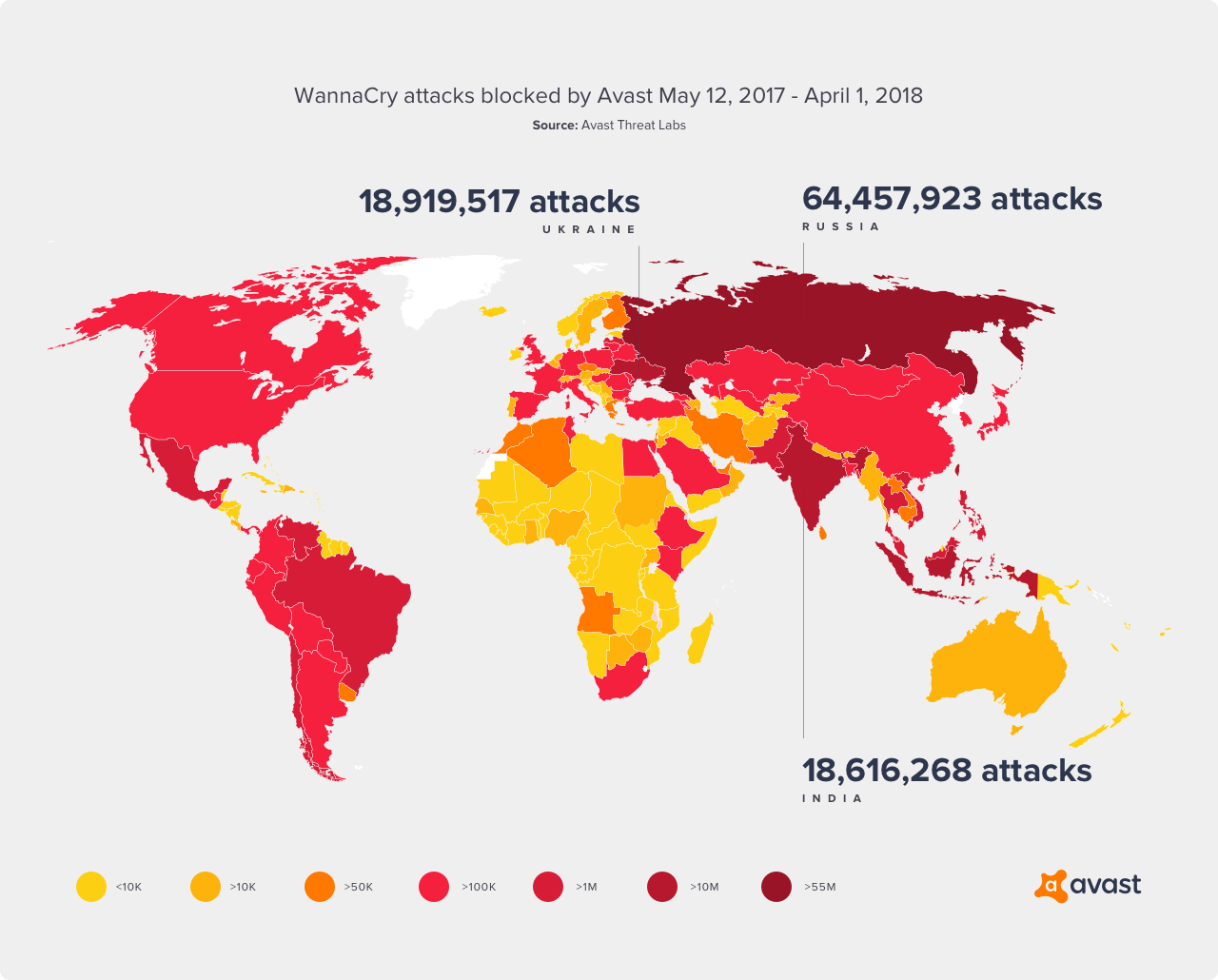

On May 12, 2017, WannaCry, the biggest ransomware attack in history, spread like wildfire around the world, indiscriminately affecting PCs belonging to consumers, businesses, hospitals, and government departments. Now, nearly one year later, the same malware continues to be prevalent, reportedly hitting aircraft manufacturer Boeing recently. Since the initial attack last year, Avast has detected and blocked more than 176 million WannaCry attacks across 217 countries. In March 2018 alone, we blocked 54 million WannaCry attacks.

WannaCry aggressively spread using the Windows vulnerability EternalBlue, or MS17-010, a critical bug in the Windows code that is at least as old as Windows XP. It allows attackers to execute code remotely by crafting a request to the Windows File and Printer Sharing service.

Aside from WannaCry, other ransomware strains, such as NotPetya, have used the EternalBlue vulnerability as well, the most notable being Adylkuzz, a cryptomining malware, and Retefe, a banking Trojan. Different hacker groups with ties to nation-states have also used the vulnerability to gather passwords, and it continues to be a useful tool for cybercriminals when spreading or targeting malware.

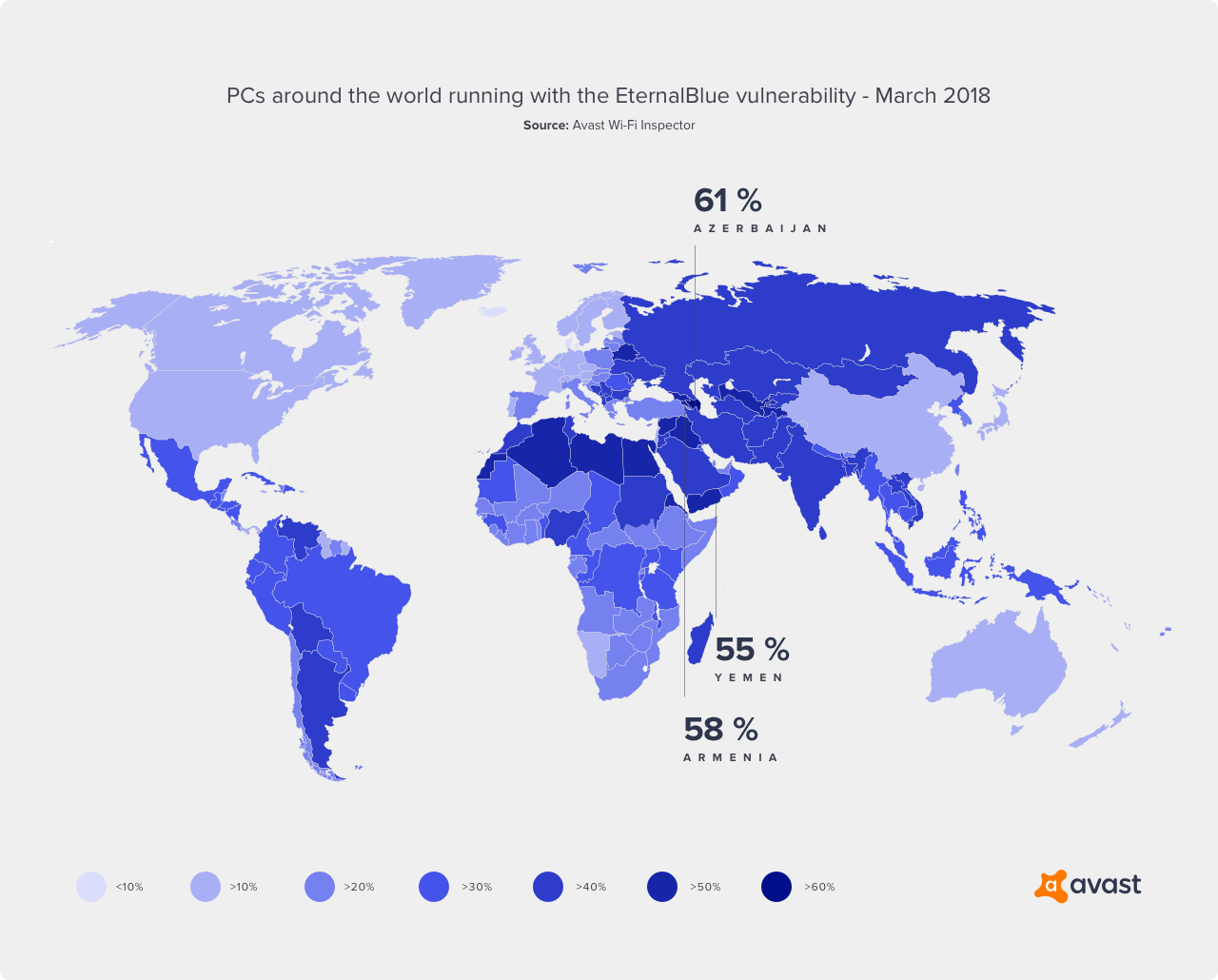

Microsoft actually released a patch for this vulnerability in March 2017 — two months before WannaCry hit — yet the ransomware still managed to attack hundreds of millions of users. This is because people failed to patch their systems. In fact, our data shows that nearly one third (29%) of Windows-based PCs globally are still running with the vulnerability in place.

Why are people not patching?

We can take an educated guess as to the most likely reasons:

- Lack of understanding around patches and software updates — many users don’t understand why they are important.

- Consumers don’t like interruptions — patching a system or program requires users to stop what they are doing and wait for the patch to download.

- Some resist change — operating system and program updates can change the familiar program environments and interfaces, which isn’t always welcomed by all users.

- Services can’t go down — organizations like the UK’s National Health Service would have to reduce its services while the update is carried out.

- Older systems are no longer supported — Windows XP is one example of a system that is no longer being supported and therefore left defenseless.

Patch perfect — what the technology industry must do better

- Educate about patches — explain the purpose for patches issued to users when they are prompted to update, using simple terms to describe the update and its importance.

- Decrease inconvenience — update in the background or in smaller doses, or by simply making people more aware of options like overnight updates.

- Offer continued support — Software developers need to consider that their systems may live beyond their intended years, thanks to robust hardware. For example, Windows XP is still being used by 4.3% of Avast users and Windows Vista by 1.5%, though Microsoft no longer supports these operating systems.

Users need education about security, as well as guidance through the necessary steps in easy, simple, and comfortable ways.

Businesses need to get serious about employee education on cybersecurity and patch management.

At the same time, software distributors need to ensure that the updates they push out are clean.

If this can be done, then the collaboration and contribution of users and the broader technology industry with security researchers and security companies is a truly powerful one in the fight against malware. We don’t yet know what impact the next WannaCry could have, but based on these critical insights from the last year, there are clear steps the technology industry can take to prevent such a major attack from happening again.