From simulated ransomware attacks to SQL injections, the activities at Cyber Shield 21 busted some of my myths about the military

Earlier this month, I had the unique opportunity to observe the National Guard conduct its cybersecurity exercises at Cyber Shield 21. This is perhaps the largest training effort of its kind, with more than 800 people across the U.S. taking part. It uses a series of real-world threats to train its “cyber warriors”. For the first time, the Guard took advantage of a virtual cyber range that the Department of Defense developed with more than a dozen contractors.

Cyber Shield has been held annually for several years, and up until 2019, it was done in person at a central Guard base, where the competing state teams were flown in to participate. However, last year, it was held completely virtually due to Covid-19 regulations. This year, Cyber Shield 21 was a hybrid event: the individual state defenders (or “blue teams”) gathered at their own bases, while key personnel came to Utah’s Camp Williams outside of Salt Lake City.

I was able to observe both sides of the event, going to Springfield, Illinois, for the defender side, and then on to Camp Williams the following day. The Utah participants included different roles: the “red team” attackers, the “white team” network owners, operations staff, legal advisors, and consultants. The event is unclassified and draws on Guard personnel (active duty and reservists) from all branches of the military as well as volunteers from private industry, including Guard reservists that work for major computer vendors, such as Dell and Microsoft. Speaking of the latter, I met people who worked at various security operations centers at both private and public entities.

Watching the activities busted some of my myths about the military. I saw plenty of cross-service cooperation — in addition to Army and Air Force Guard personnel, there were participants from the Navy and Coast Guard too. It was a true public/private sector partnership — many of the Guard that I saw were employed by IT departments and by tech vendors in their day jobs, since they only work part-time as reservists, serving a weekend a month plus some time in the summer.

The officer in charge was Lieutenant Colonel Brad Rhodes, who works as head of internal cybersecurity at a tech firm in Colorado. This year’s event was his sixth Cyber Shield engagement.

The two leaders of the event, George Battistelli, the exercise director (left) and Lt. Col. Brad Rhodes, the officer in charge (right).

Part of the partnerships also extended to cybersecurity specialists that come to the event from other countries. Rhodes told me that “the Department of Defense (DoD) uses numerous commercial systems and our adversaries know that. We can bring in real world lessons and teach our defenders what they need to be looking for during Cyber Shield. Having to collaborate virtually — and securely — is a further way to simulate what happens during an actual attack.”

Major General Rich Nealy, one of the Guard officials that visited the Springfield operation, said, “Cybersec is on the front page of every newspaper today. This exercise is typical of a fight that we have to win, where the terms are not well known going into battle.”

General Rich Nealy interviewing the Guard members under his command in Springfield, Illinois.

Making use of modern cybersecurity training techniques

The simulated attacks at Cyber Shield are purposely designed to mimic actual real-world conditions. For example, one of the red team members takes on the role of an employee clicking on a phishing link that deposits malware on the network. The defending team members must then find this malware before it spreads across their network and infects web servers and other applications.

There are also ransomware attacks and data that is stolen and posted on a simulated dark web. They even included a PrintNightmare scenario, which is impressive, given that this attack only happened a few weeks before the event. Another scenario modeled what happens when someone tries to poison a water supply. Additional attacks are more mundane, such as SQL injections and privilege escalations.

There are more than 50 different roles played by the participants, including actual representatives from the federal Fusion Centers where cyberthreat data is shared among government agencies. Part of the challenge of these simulations is that the simulation also uses real network traffic to obscure the malware moments, which is very much the case in the real world.

Prior to attending the event, I had believed that DoD cost overruns and contracts could be done more cheaply by using private businesses. However, the backbone of the exercise was what’s known as the Persistent Cyber Training Exercise (PCTE). It’s a huge cloud-based application that runs the attacks, and the Cyber Shield event is the largest operation conducted across this network, consuming more than 3,000 virtual machines and a petabyte of storage.

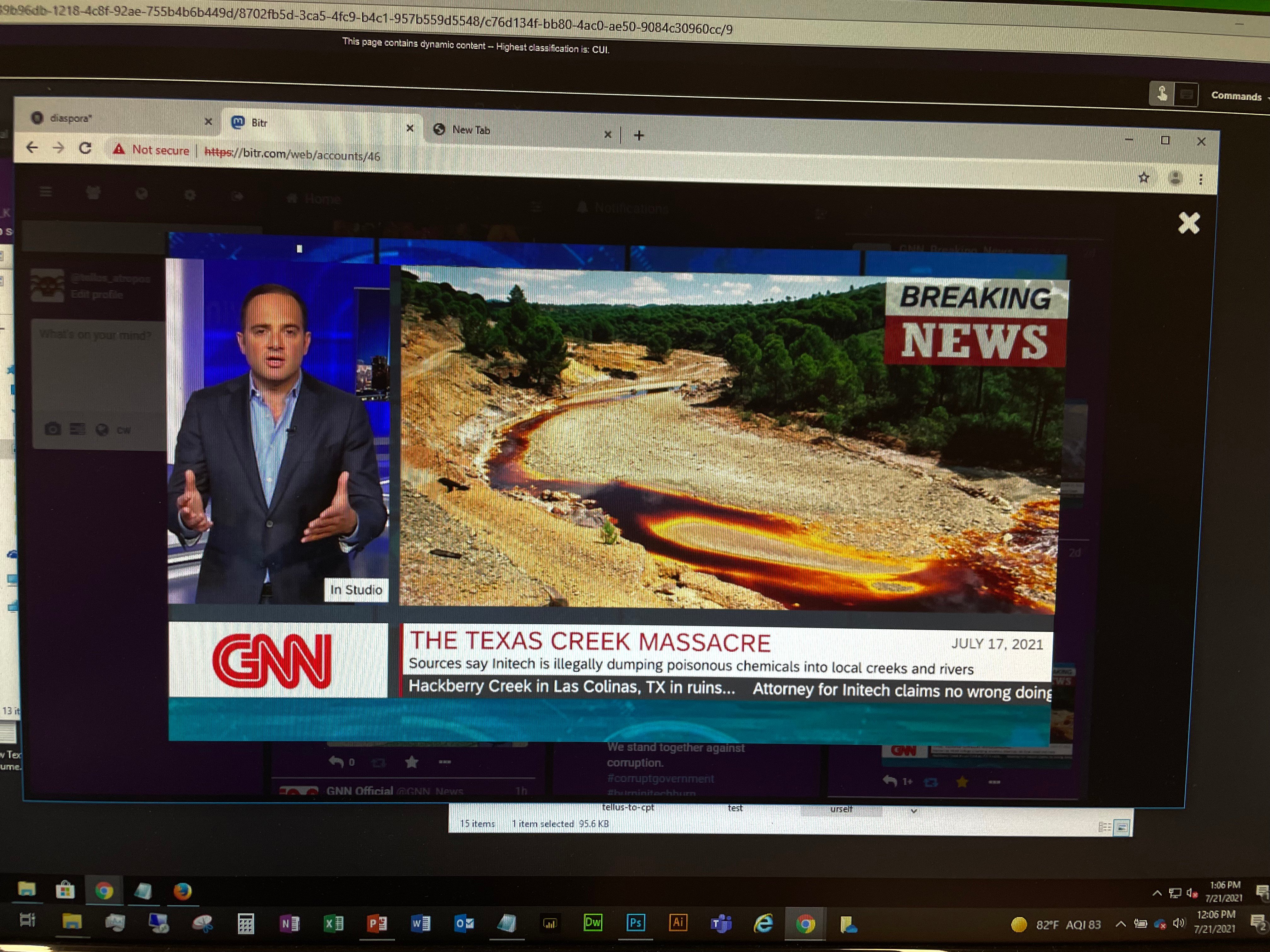

Demonstrating the extent of the simulations, down to a fake news clip from “GNN” that was distributed across the network during the exercises.

How are “cyber soldiers” trained?

During the two-week event, there were numerous different types of exercises, including a “purple” day where both defenders and attackers work side-by-side to share tips and techniques. One of the days is devoted to the NetWars competition (the Illinois team came in third place out of all the Guard state units competing — something they were obviously very proud of). There are also days spent consuming commercial courseware so that Guard members can obtain their Security+ credential from COMPTIA or other SANS certifications.

“We know that the threat actors are collaborating way better than we are, and this gives us a chance for us to work closely with our partners and in realistic scenarios and build trust and deeper relationships,” said Rhodes. This building of trust is important because you want teams to learn from each other, rather than depend on a single analyst who may or may not be on duty or leave the Guard when an actual threat occurs.

“This is the future of how wars are going to operate,” said Joe Daniels, a sixth-year Cyber Guard participant whom I met when I was in Springfield. He’s the Chief Information Officer for the Illinois State Treasurer and is also a sergeant in the Illinois Army Guard. “But this is a different battlefield and I enjoy being a part of shaping that and love training people. It really prepares you for the real world and addresses attacks that we see everyday across our own network.”

How Cyber Shield helps Guard members grow their careers

Many of the active duty Guard members I spoke with at the event have served in various long-term deployments all over the world that take them away from their families for a year. One Guard reservist that I met began his Guard career when he was working for Microsoft, and has continued with his service at another security firm. To me, this demonstrates not only the value that these individuals place on their service but also the importance of the Cyber Shield exercises and how it helps members train their colleagues.

Women in tech at Cyber Shield

Last year’s officer in charge, as well as several leadership roles at this year’s event, were held by women who have been with the Guard through many Cyber Shield exercises. For example, Major Dana Sanders came from the Kentucky Guard and is responsible for supervising the threat narratives, creating the scripts and running the exercises. Another participant obtained her doctorate in computational biology and did her dissertation on how virus host immune systems respond to infections. She now works as a security analyst for a telecommunications company and is a Guard reservist. A third started her career as a lawyer but then got interested in cybersecurity, and she now works for the Pennsylvania Guard full time running training exercises.

When you think about the U.S. military, you can understand the greater context that this massive training event fits into. After all, they take fresh-faced teenagers and turn them into battlefield-ready cyber soldiers. It was inspiring to see so many dedicated men and women who are willing to give so much time to support this effort, year after year.

Note: If you are interested in volunteering for Cyber Shield 2022, please send an email to Major Christine Pierce at christine.m.pierce.mil@mail.mil, who will be happy to discuss your participation. (She has approved the publishing of her email address.)

Image credits: David Strom