Reviewing the current status and continuing development of prominent tracking apps

After the Covid-19 outbreak, several groups got going on developing various smartphone tracking apps, as I wrote about last April. Since that post appeared, we have followed up with this news update on their flaws.

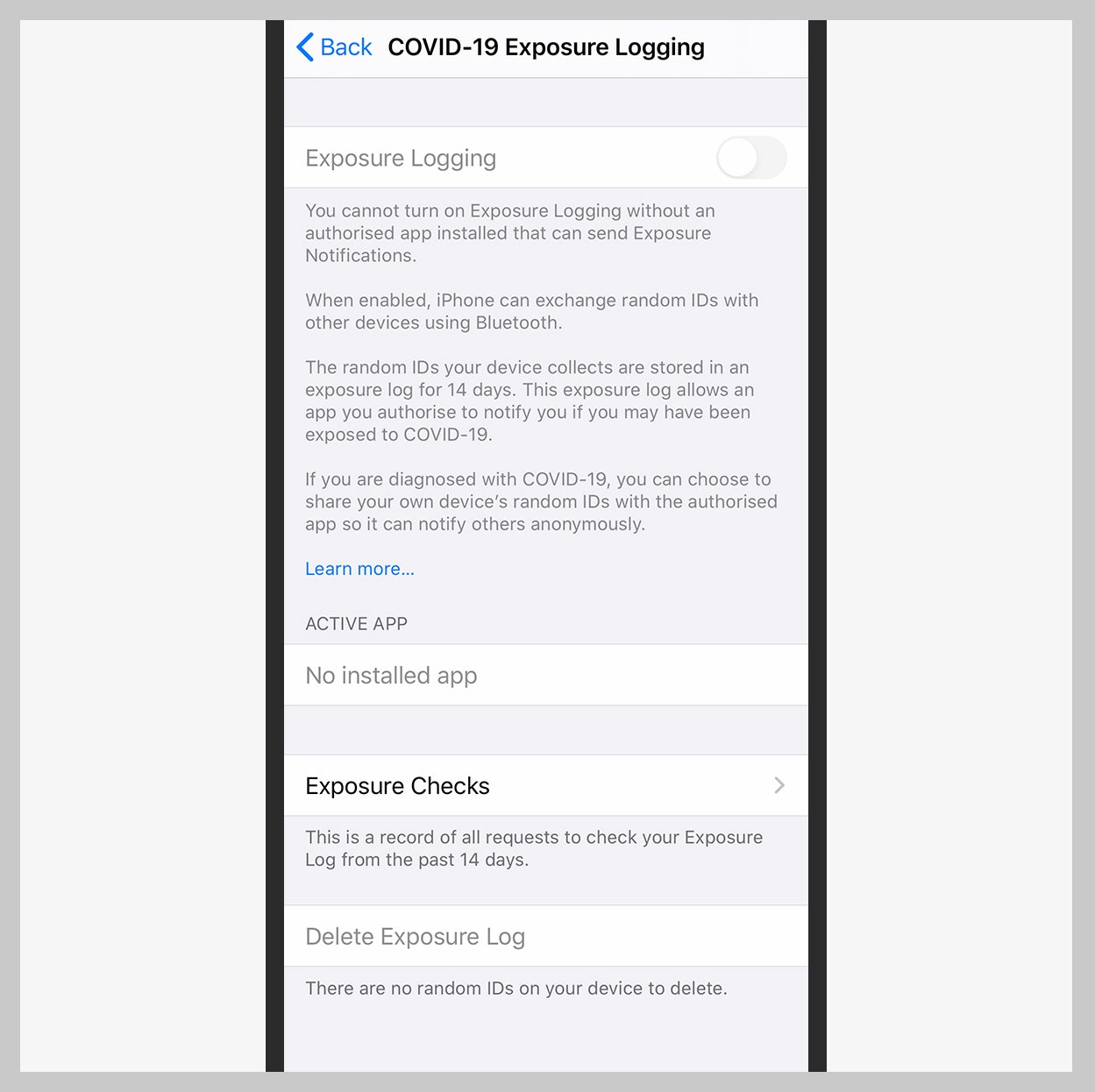

Given the interest in using so-called "vaccine passports" to account for vaccinations, it is time to review where we have come with the tracking apps. A good place to start is this post on how our phones will actually use these apps for contact tracing. On either iOS or Android, search for “Exposure Notifications” if you want to enable these, or check to make sure your intentions are reflected accurately.

Image credit: WIRED

This Wikipedia page lists nine different application frameworks that are under development across the globe as well as what has been deployed by dozens of countries and, in some cases, other localities. Several of them have licensed various open source code repositories (such as CovidSafe’s CommonCircle, SafePaths and Pathcheck.org) or are using the Google/Apple framework officially known as the Exposure Notifications System. Apple has used interfaces from this code since coming out with iOS v13.5 last summer. Android phone makers have not uniformly implemented the Google code.

One of these vaccine-related apps that I mentioned in a recent post is CommonPass, which is being developed with help from the Mayo Clinic. In this post, their efforts are described to develop a comprehensive health app that will be called HealthCheck. It will include tests for common sexually transmitted diseases along with Covid-19 vaccine workflow details.

Singapore and contact tracking

Furthest along on the tracking front is what is happening in southeast Asia. Singapore has been using apps based on OpenCovidTrace, which interoperates with various frameworks, including the Google/Apple and EU DP-3T efforts. That “universal interoperability” was the design goal from the start, as well as to preserve individual privacy through judicious use of encryption and by limiting storing any personal data to the phone’s memory and not in any cloud repository.

Other apps have been developed using this code, including ones for New York and Australia. Singapore actually uses its own tracking protocol called BlueTrace in its app called TraceTogether. Since its deployment last spring, almost 80% of the island nation’s population has either adopted the mobile app or carries a smart token that is produced by a dedicated wearable device. One reason for its popularity is that the government requires the token to enter public buildings. (Many American universities are also using Covid-19 tracking apps to limit building access.) Positive test results are kept for a month and then deleted. Interestingly, the police can tap any data gathered by the app for criminal investigations.

The situation in Singapore points out the complexities about these apps: you need to understand the wider context of their use and how your data will be consumed by the government for non-health-related purposes. One issue that still remains is whether your government’s health agency has enough manpower to do anything with all the positive contacts it collects. In many situations both in the US and the EU, health agencies are overwhelmed and can’t follow up quickly enough to be very effective.

But wait, let’s talk about malware

Of course, bad actors have been producing fake Covid-19 tracking apps almost since the pandemic began. This post summarizes a bunch of Covid-related malware apps, including banking trojans, Covid-19 mapping dashboards as well as more recent versions of bad tracking apps. There have also been numerous phishing exploits that have filled the security literature with Covid-related subject lines. Some of the phishing attempts are noteworthy. For example, instead of using Covid-19 information to trick users, criminals have used Covid-related school updates and job listings.

But data breaches have leaked patient test results, such as what was recently reported in India that was discovered by security researchers.

The bottom line is that tracking Covid-19 infections is still far from perfect, and unfortunately, the process remains fraught with privacy risks. While the apps have generally done a good job at keeping users’ data private, there are still many ways this data can be abused by various organizations, including authoritarian governments.