The utilization of BBSs by trans people in the 1980s and 1990s gives a glimpse into just how important the internet would prove to be for this historically marginalized community.

This article is part of a multi-article series celebrating Pride month and the role the internet has played in the history of the LGBTQIA+ community.

The internet has played an outsized and very visible role in the massive political and social gains of transgender people over the past two decades. But while it’s easy to point to modern-day social media and smartphones as instrumental tools for the trans community, trans people have actually been utilizing the internet to connect, learn, and organize since the 1980s.

Dr. Avery Dame-Griff, PhD, is a lecturer in Women’s and Gender Studies at Gonzaga University. He’s also the founder and primary curator of the Queer Digital History Project, an independent project tracking queer* digital culture from the 1980s to the 2010s. His forthcoming book focuses on the relationship between the “two revolutions” of the transgender political revolution and the computer revolution.

Dr. Dame-Griff’s research and archival work digs extensively into the earliest communities of trans people online: BBS or the “Bulletin Board System.” The BBS was a precursor to the modern world wide web and social media. Launched in the late 1970s by computer hobbyists, BBSs allowed users to dial a number through their modem and access an online, text-only “bulletin board” where users could post messages. By the mid-to-late 1980s, as the technology needed to access BBSs became more affordable and accessible, BBS groups focusing on niche interests — including transgender communities — were popping up across the US and, soon, the world.

These early online trans communities were secretive and ephemeral by necessity, Dr. Dame-Griff tells Avast. Trans women in the 1980s were likely to be presenting publicly as men, oftentimes with wives and families, and exposure could result in them losing everything — their jobs, their families, and even their lives. Some lived as “crossdressers,” allowing themselves to dress in women’s clothing at home (maybe with their spouses) but rarely, if ever, in public.

Image courtesy of the the Queer Digital History Project

Image courtesy of the the Queer Digital History Project

Finding community

But even with such high risks, trans people living in the pre-world wide web world were still finding ways to live in their truth and find community. Physical objects like high heels and pearls were stored in locked boxes in the backs of closets. Communication was done through P.O. Boxes, because even a voicemail posed too great a risk of exposure. And then came the BBSs.

“The BBSs solved a lot of the problems around privacy,” Dr. Dame-Griff says. “When you dialed into a BBS, it was just a number on a phone bill. There was no record of who or what it was. Plus, digital files are much easier to hide and get rid of; a file named ‘Budget 1986’ looks innocuous and a spouse would think nothing if they saw it.”

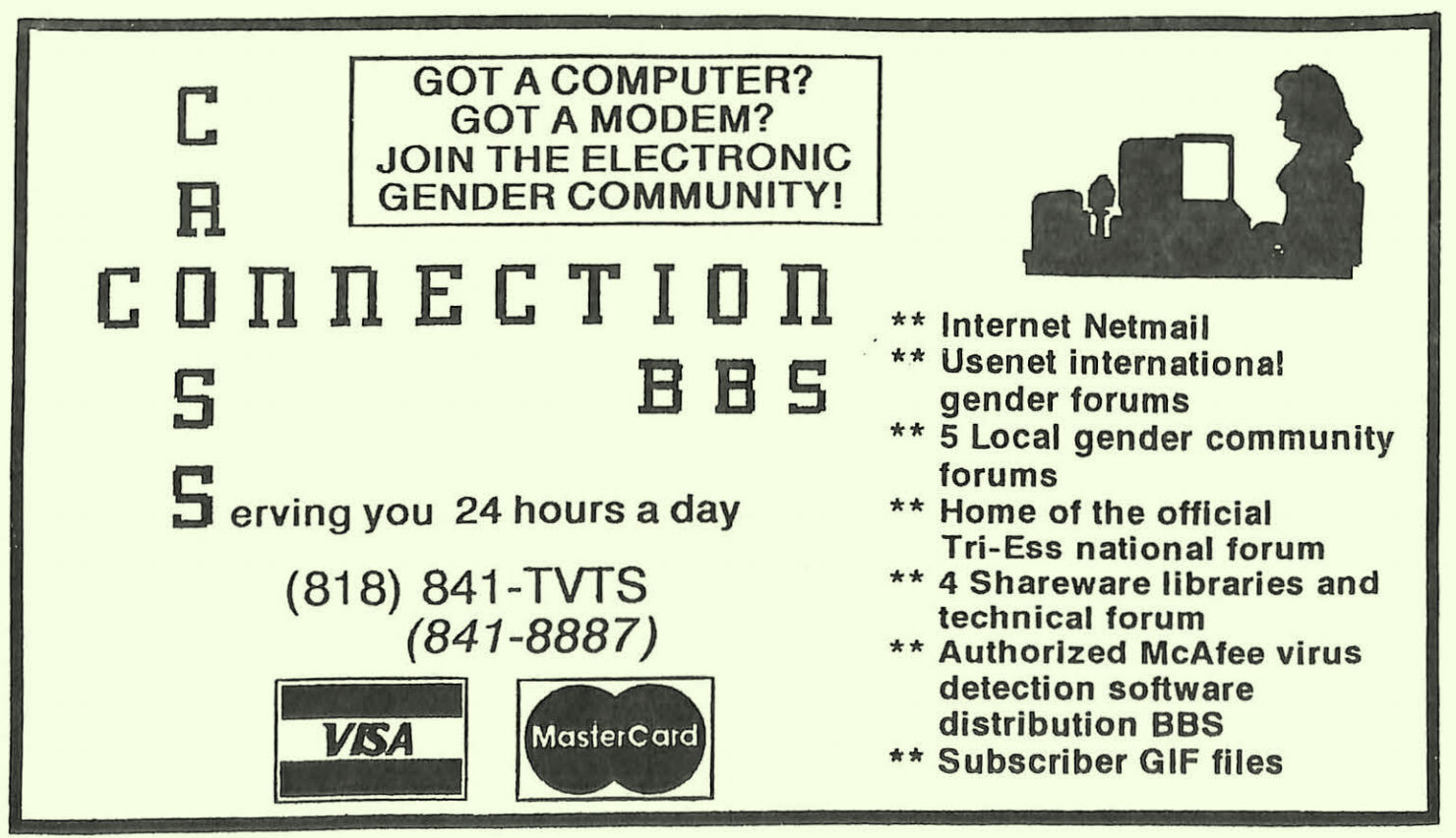

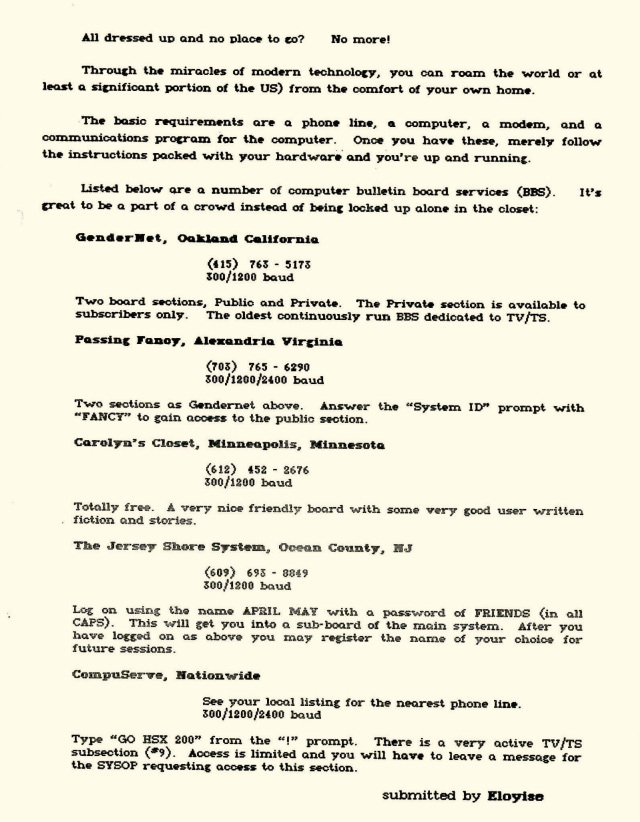

As a result of this deep need for secrecy, Dr. Dame-Griff has had to rely heavily (and somewhat ironically) on paper records to locate and gain insight into these BBS communities. Magazines that specifically targeted transgender communities (usually transgender women) would list the names and access numbers of trans BBSs in the back, along with ads for feminizing medical treatments, clothing stores catering to trans women and cross dressers, services, and personal ads. People with the means to access a personal computer and modem could dial in and join other transgender, transsexual, or cross-dressing peers. “In the 90s, almost every major trans magazine had explainer articles on how to use the BBS,” Dr. Dame-Griff says.

Image courtesy of the Digital Transgender Archive via the Queer Digital History Project

Image courtesy of the Digital Transgender Archive via the Queer Digital History Project

Secrecy in a pre-digital world

Dr. Dame-Griff points to one BBS, Feminet, founded in 1988, which even had a “false front” before people could gain access to the real board. Similar to the back room hidden door patrons might need to access a pre-Stonewall gay bar, users trying to access Feminet would dial in and be directed to a completely different site. There they would be asked for a password, which was listed in the back of “TV-TS Tapestry,” one of the major transgender zines of the time. If they didn’t have it, they’d be bounced.

While magazines were a major way that trans people found information about the BBSs in the 1980s and early ‘90s, they also engaged in creative guerrilla marketing.

“Trans groups would sneak fake dewey decimal cards with information on how to access their BBSs into the card catalogs in the library,” Dr. Dame-Griff says. “It worked as long as no librarian checked.”

Once inside a BBS, trans women found something that was often lacking in their in-person lives: Community. Resources. Women like them. Some, Dr. Dame-Griff says, would even dress up to go onto the BBS, years before the invention of webcams. No one could see them in their heels, pearls, and dresses, but they still wanted to embody their womanhood while connecting with community.

Image courtesy of the Internet Archive via the Queer Digital History Project

Image courtesy of the Internet Archive via the Queer Digital History Project

Trans BBSs also created a huge opportunity for political organizing. After mainstream pushback to organizing in the 1970s, Dr. Dame-Griff says, trans people largely stepped back from trying to gain political gains in the 1980s. But BBSs provided a way to not only link trans groups separated by geography, but also re-engage trans people who had undergone medical transitions and were “woodworking,” a term used at the time to describe someone who underwent medical transition, effectively “passed” as their gender, and wasn’t known to be trans.

Dr. Dame-Griff tracked down typewritten digitized archives of the Twenty Minutes newsletter that included letters from a woman named Louise L. Raeder, who founded the trans BBS “Us Too” in 1989 with the goal of propelling trans political and advocacy “like a rocket.” She was an early adopter who recognized the immense power of the internet to expand trans rights; a power that society didn’t see come into full effect until the 2010s.

The utilization of BBSs by trans people in the 1980s and 1990s gives a glimpse into just how important the internet would prove to be for this historically marginalized community. The search for identity and community is strong in all humans, but the internet has made it that much easier for those who don’t fit neatly into the social norms, whether they’re computer nerds, crossdressers, or trans women who just want to live their truth.

*A quick note about language: terms referring to different elements of the LGBTQIA+ community are very fluid, often changing drastically over time and perceived differently in different places. Because this article is looking at an historic period of time, the words and archival sources sometimes use words that are no longer in common usage or are even considered offensive now. Please know that the intent of this article is to celebrate and share an element of LGBTQIA+ history that is often overlooked and that all word choices are made with care and consideration.